That Sunday evening of November 23, 1980

INGV has created a web portal on the Irpinia earthquake with extensive scientific insights, testimonies, and a story map

The news breaks a few minutes before 8 p.m., but it takes most of the night to realize its true extent. Teleprinters continuously type distressing dispatches. They are still vague fragments: hard to understand what has happened based on a contradictory number of casualties, still minor but foreshadowing disaster. Only later, around 11 p.m., are the pages of the newspapers filled with the tragic news. It's a dull Sunday in Italy, rather uneventful.

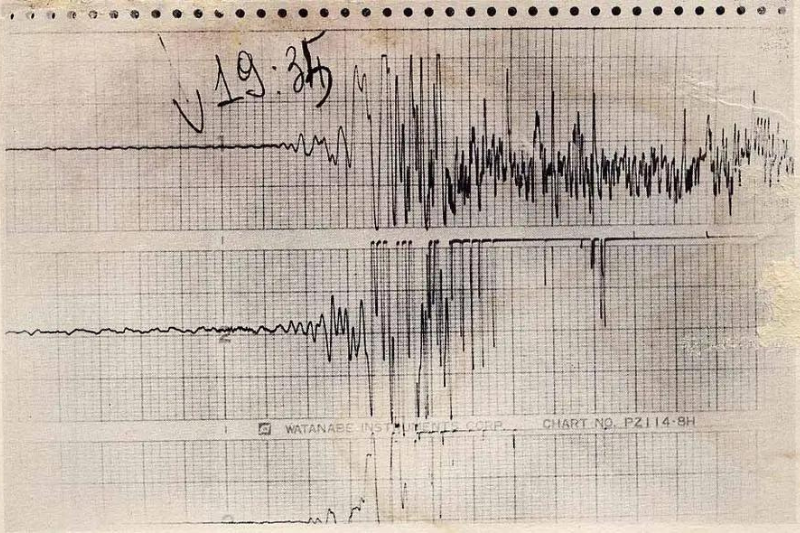

Thatcher is in Rome for an interview with President Forlani, and Italian television is airing the Juventus-Inter football match. During one half of the game, it is 7:34 p.m., and a minute-long horror starts: a seismic wave of unprecedented power is shaking the earth. Southern Italy is in shock, with Campania and Basilicata seemingly the hardest-hit regions. Immediately, there is talk of dozens of deaths. Within just an hour, there are already hundreds, the number increasing by the minute: terrible predictions are made.

The first news comes from Naples, where some buildings have collapsed and people, terrified, have poured into the streets. Infinite columns of cars are seeking a way out to the countryside; traffic is jammed. The radio said the tremors might happen again. Everywhere, the rescue operations seem difficult. Electricity and telephone lines are down. From Rome southwards, there is silence. Communications between the earthquake areas and the operations room at the Viminal Hill are down, and there is no chance of restoring them. The peninsula is cut in half, this time by the earthquake.

First aid.

Upon the first news of the disaster, civil defense mobilizes men and means, putting together what little it has available. Some convoys leave from Florence, others from Bologna, while army units, fire brigades, mobile Carabinieri, and police battalions leave Rome. On the other hand, trains are blocked; traffic to the south is completely paralyzed. Convoys are stopped at Formia station to give engineers time to conduct inspections. Poor and incomplete news continues to arrive.

The focus of attention is not only on Naples; now, there is a suspicion that inland, Basilicata, and in the mountains of Irpinia, the disaster turned into a catastrophe. The few rescue teams that at once took action are trying to open a passage to the mountain territories. The disaster map stretches from Salerno to the area of Sannio, from Vallo di Diano to Mercato San Severino. Late in the night, the names of the devastated towns, unknown to many until then, are added. In the affected areas, people do what they can with great improvisation, and the first witnesses begin to arrive, reporting horrifying details of the catastrophe.

Around 11:23 p.m., the Ministry of the Interior reports that the most severe situation occurred in three provinces: Avellino, Potenza, and Salerno. Press dispatches do not yet give a complete picture of what has happened, but a catastrophic scenario appears slowly: it is hard to believe. Requests for help are coming in from everywhere. From Ariano Irpino to Telese, from Ricigliano to San Gregorio Magno and Palomonte. A military radio broadcasts reports of casualties from Rionero in Vulture. There is still hope that the tragedy is limited to the things known. Shortly before midnight, the first death toll for the city of Naples appeared: thirty-eight casualties. They will grow later in the night. News continues to arrive at the operations room of the Viminal Hill: the night is restless, the hours pass between attempts, not all successful, to organize rescue interventions. The affected areas are covered in fog. An eerie silence descends upon the night.

Affected areas.

Calls for help are multiplying: photoelectric lights, men, and excavation equipment are insufficient. Only in the early hours of Monday is it possible to obtain a geographical map of the destruction. Naples, Caserta, Benevento, Salerno, Avellino, Potenza, and Matera are the most devastated provinces—the poorest. One thousand confirmed deaths are now being reported, but it is clear that this is the tip of the iceberg. The rescue machine is at work but is still weak and slow. Radio amateurs are rushing to help as in any natural disaster. The list of destroyed towns, largely incomplete, lacks the areas where the earthquake hit hardest: Sant'Angelo dei Lombardi, Santomenna, Lioni, Calabritto, Balvano, and Conza. Upper Irpinia is silent. A first estimate of the area affected by the earthquake is tried: it should be an area of twenty-six thousand square kilometers stretching from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Adriatic Sea. The affected population is around seven million people divided into approximately 650 Municipalities.

Taken from "I GIORNI DEL TERREMOTO " by Pietro Magi – Edizioni BS/DOCUMENTI – 1980

On the 40th anniversary of the November 23, 1980, earthquake, the National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology (INGV) created "Terremoto80," a web portal based on three keywords: science, memory, and testimony. The different sections contain scientific insights into the earthquake, video interviews with the testimonies of people who experienced it, and memories and recollections of the early 1980s.

Finally, story maps narrate the impact of the earthquake, the establishment and development of the National Seismic Network (RSN), and seismic activity in Italy from 1980 until today.

Go to the website: http://terremoto80.it